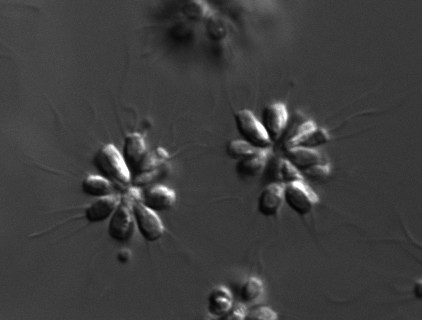

An article published in the journal “Science Advances” reports the results of a study on microbes of the species Salpingoeca rosetta (Photos of colony and specimen Mark J. Dayel) that offers evidence that individuals exchange electrical signals they use to coordinate their behaviors. Jeffrey Colgren and Pawel Burkhardt of the Michael Sars Centre at the University of Bergen, Norway, used a newly developed genetic tool to examine the behaviors of colonies of these microbes that belong to the group of choanoflagellates (Choanoflagellata), the eukaryotes most closely related to animals.

The result of the study was the discovery of exchanges of signals similar to the ones used for nerve transmission between neurons and the contraction of muscle cells in multicellular organisms. These signals use so-called calcium channels since this element is an important messenger within the cell. This suggests an ability to coordinate the movements of multiple individuals that blurs the boundary between unicellular and multicellular organisms.

The evolution from unicellular to multicellular organisms is not yet well explained. Many studies are trying to shed light on the mechanisms that led to this crucial step in the history of life on Earth and in recent years, progress was made. One possibility is that animals evolved from organisms similar to choanoflagellates, which are unicellular.

Choanoflagellates have morphological similarities with choanocytes, a type of cell that exists in sponges, and the species Salpingoeca rosetta shows that it’s at what can be considered an initial level of cellular specialization. For this reason, they’re the subject of various studies on the evolution of multicellular organisms.

This study allowed to detect the electrical signals that different cells of a colony of Salpingoeca rosetta exchange and use to coordinate their behaviors. According to the authors, this discovery suggests that the ability to coordinate movements at the cellular level precedes the evolution of the first animals.

The ability to coordinate the movements of Salpingoeca rosetta within a colony may offer greater efficiency in feeding and compact the colony, providing greater safety against potential predators. Even in the laboratory, the environments in which these choanoflagellates were studied are not static and the reactions of the microbes suggest that there’s a selective pressure in the regulation of certain processes connected to feeding and protection.

Jeffrey Colgren and Pawel Burkhardt intend to further investigate the ways in which signals are propagated between the cells of Salpingoeca rosetta and study other species of choanoflagellates to verify if similar mechanisms exist. Other researchers are studying the DNA of choanoflagellates and in particular the species Salpingoeca rosetta to understand the genetic similarities and differences with animals. There’s still work to be done to understand how multicellular organisms emerged, also because choanoflagellates are closely related to animals and the history of other multicellular eukaryotes must be reconstructed as well.