An article published in the journal “Nature Communications” describes a genetic research on a European hominin whose bones were found in Germany in the Hohlenstein-Stadel cave. This individual is about 124,000 years old and is a Neanderthal but his mitochondrial DNA is different from that of the others of his species. According to the researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, this indicates a crossbreeding with African hominins closely related to Homo sapiens.

In recent years, the great advances in paleogenetics, a specialization concerning the DNA of ancient organisms, even extinct ones, are providing many new data on hominins, which taxonomically are a tribe called technically Hominini within the hominid family, which includes the various species of the Homo genus. Samples of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA samples are slowly allowing to understand the relationships among the species with the complication of various crossbreeds that are sometimes discovered.

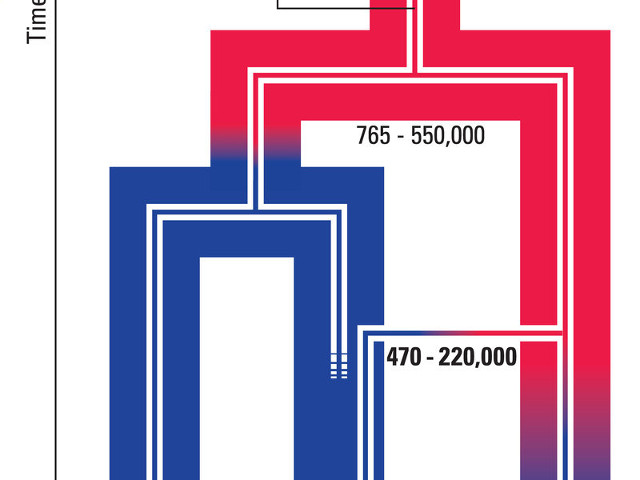

According to the results obtained at the Max Planck Institute in a previous research published in the magazine “Nature” in 2015, Homo sapiens’ ancestors separated from those of Neanderthal and another species called Denisovans between 550,000 and 765,000 years ago. These two species are closely related but another mitochondrial DNA-based research showed that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals separated “only” 400,000 years ago, in short those are apparently very different results.

One of the hypothesis was that at some point Neanderthals crossbred with other hominins genetically more similar to Homo sapiens and this seems to be the case of the individual found in 1937 in the Hohlenstein-Stadel cave and referred to as HST. A radiocarbon dating gave inconsistent results indicating possible contaminations and that the examined femur could be too old to use that type of dating.

The dating was carried out through an estimate of the mitochondrial DNA mutations at 124,000 years. It’s not certain that the rhythm of mutations in Neanderthals is the same as in modern humans but the estimate should have at least a fair approximation. This is important because HST lived about 45,000 years before the arrival of the first Homo sapiens in Europe, yet his mitochondrial DNA has characteristics that are different from those of the other Neanderthal tested. Actually, a separation between the two genetic lineages according to the estimates took place at least 220,000 years ago.

The scenario emerging from genetic comparisons of 17 Neanderthals, 3 Denisovans and 54 modern humans is that there was a migration from Africa of a group of hominins who crossbred with Neanderthals. This may have happened between 220,000 and 470,000 years ago with a probability peak around 270,000 years ago.

This migration left few genetic traits that only today have been discovered. The researchers can say that these African hominins were closely related to modern humans but it’s unclear what species they belonged to. The approximation in estimating that migration’s period makes the research more difficult.

One of the conclusions is that the migration involved a relatively small group of hominins. On the other hand, the population of Neanderthals was probably larger than it was thought because it absorbed almost entirely the migrants in a limited part of it.

Mitochondrial DNA can provide limited information but is easier to recover than nuclear DNA because it’s much smaller and is present in multiple copies. The Max Planck Institute is one of the most advanced in the world in the field of paleogenetics if not the most advanced but retrieving nuclear DNA from such ancient bones can be impossible today.

Further investigations into this migration of hominins from Africa would also require genetic material from more individuals. This is a long task that also requires a bit of luck to find the DNA needed by the scientists but this research has opened new possibilities for studies.

Permalink